Film, Book, Other: Incels and Zombies

What we watched, read, listened to and gazed at in January.

Film

Tom: Three Colours: White (1994) Dir. by Krzysztof Kieślowski

Amy: 28 Days Later (2002) Dir. by Danny Boyle

Tom: White follows Blue. Kieślowski’s film on the French Revolutionary pillar, Égalité follows his equally twisted exploration of Liberté. I was tentatively able to stomach Julie's journey in Three Colours: Blue, to learn to view the death of her husband and child as a form of liberty, but Karolin's equality is much harder to reconcile. The crumpled, down-trodden, damp figure of a man at the start of the film suffers his greatest humiliation when his wife reveals his impotence to a full court to justify their divorce. From there he sinks lower and lower and discovers the only way to claw himself from rock bottom is revenge. By the end of the film, Karolin has enacted, in his mind at least, a form of equality. He believes his actions to be justified, but the cruelty and venom drips from the screen.

Kafka’s influence is present right from the start of the film, with Karolin being forced to fight bemusing bureaucracy at a court and a bank, before undergoing his own twisted metamorphosis. Imagine your horror however, if at the end of his trial, Josef K donned a police officer's uniform, climbed the stairs to the judge's table and turned, with great cruelty and impunity, from prosecuted, to prosecutor.

Amy: I had never watched a zombie film - or even a rage virus one - until a few weeks ago. On a quiet Friday night, something came over me, and I decided to give 28 Days Later a chance. I found myself enjoying its grit and wit, and the range of familiar touch points in both time and place. Not usually liking gore, the cinematography came as a welcome surprise, and actually created a more raw and real sense of fear. In true panic, reality becomes messy. The violence jumps from between blurred lines and stamps itself onto your brain like the flash from a camera. Similarly, the reported financial issues and changes to the ending helped add a palpable uniqueness to the whole project. Accidents and mistakes in art often create a richer whole, a deeper, more expansive vision than sterile perfection. The film’s insights on the rapid emergence of fresh hierarchies and systems of oppression feel relevant to today’s world, and highlights how division can thrive in any apocalypse, and will emerge even in the face of an undeniable common enemy.

Book

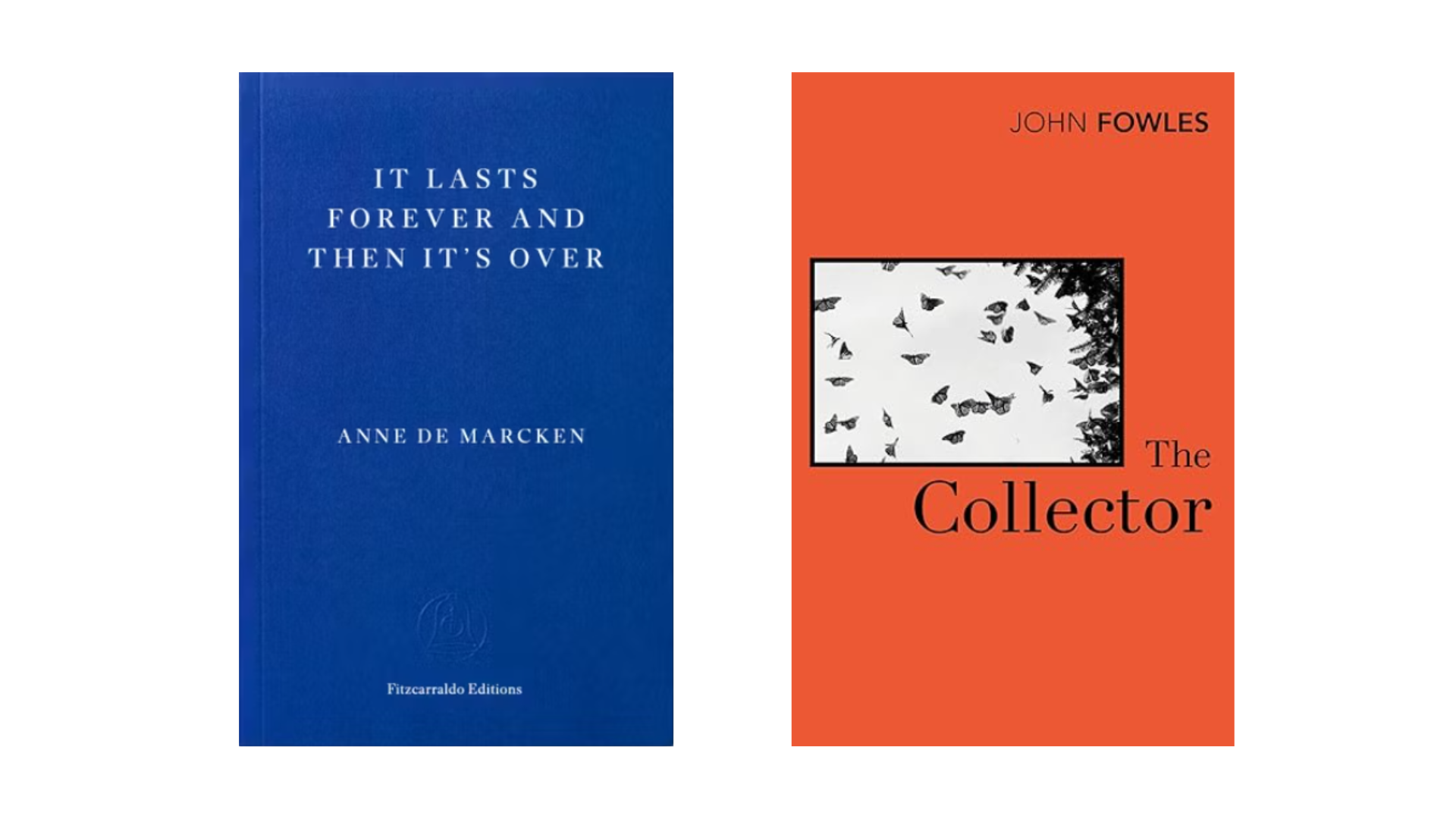

Tom: The Collector by John Fowles

Amy: It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over by Anne de Marcken

Tom: The use of first person in John Fowles' The Collector is one of the most effective I have ever read. In modern novels, first person narratives have more and more become the norm. It allows authors to more easily reveal the inner thoughts and workings of their characters. The Collector inverts this logic, and uses the main character's perspective to conceal and obscure. We are left to read between the lines of Frederick Clegg’s insipid, proto-incel, rambling grudges and justifications, and infer ourselves just how sinister he is. When the perspective shifts to Miranda, the disparity in the clarity and richness of her emotions is immediately apparent, and we are forced to re-evaluate everything we have read so far.

Explorations of the rapidly evolving social order that the 1960s brought to England are peppered throughout the plot, giving it a strong sense of time and place, similar, in a roundabout way, to the feel of Mad Men. You can reach in and run your fingertips down Frederick’s clothes, you taste Miranda’s food, you breathe in the smell of the cottage and long for the freedom of the night air.

As I write these passages I notice the similarities between the villainous protagonists of both The Collector and Three Colours: White. Frederick and Karolin both face difficulties interacting with the woman of their obsession, and leap to extreme lengths to achieve what they believe is just, what they believe is owed to them. They are precursors of the modern incel, righteous in their victimhood, firing a barrage of blame at society, the opposite sex, and anything in between. Crucially however, never at themselves.

Amy: I first encountered It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over when sheltering from the rain one Sunday a few months ago. It was that torrential sideways rain that offers no escape other than to retreat indoors. Browsing book shops is a favourite weekend pastime of mine, but this was definitely a necessity over choice. I threaded my way through the overcrowded space towards the small stack of Yves Klen Blue Books which have a habit of drawing me in. Fitzcarraldo Editions are an independent publishing house who champion experimental and unique writing, including one of my favourite reads of recent times: Mild Vertigo by Mieko Kanai. It doesn’t hurt that they also look incredibly chic. Skimming over the blurb, I liked the sound of this mixed-up, upside down world. Like a strange dream. Sadly, I wasn’t in the market for a new book on that particular day, but I made a mental note before dashing for the tube.

Fast-forward to the first week of January. After a busy few days back at work, I decided to treat myself by going into Libreria, one of my favourite book shops in London. As soon as I entered its curved, orange interior, finding this intriguing book became my object. I could picture it but I couldn’t quite align the words of the title. The shopkeeper glanced at me with a helpful gaze. I’m looking for a book and this is not what it’s called but it’s something along the lines of You Live For a Long Time and Then You Die”. She smiled, turned to the shelf behind her, and handed me what I was searching for.

I read it quickly. Its pace slows and quickens and is arresting in its boldness and structure. This is a melancholic yet playful story that deals with the grief of losing yourself, the places and the people that you love. Much of Anne de Marcken’s writing is quote-worthy, but one of my favourite passages explores a childhood memory:

“He is the centre. My body flies out from him. I am a flag, a ribbon, a blur of light…trees and roads growing smaller below and near the apex of my arc I will exit the atmosphere into cold silent orbit”

After finishing the book, I was shocked to discover the volume of the reviews on Goodreads describing it as a zombie novel. It made me panic slightly - am I the most recent victim of the post-literate society, unable to critically digest my cultural consumption? Yes, there were zombie references, but to me, they at least on the first read, seemed metaphorical. I saw the setting as an in-between space. The broken skeletons of reality. A place where there are new truths which we as the reader must come to accept, whether we like it or not. Like a crow living inside your chest. I’m going to blame it on my lack of knowledge of zombie culture. And anyway, I think It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over is one of those books that you have to let wash over you the first time you read them, giving it time to linger in your mind and body, before re-reading over and over again.

We live in uncertain times and de Marcken manages to tap into that existential anxiety whilst steering us back to a reassuring stillness. There will always be a book shop where you can shelter from the storm.

Other

Tom: Champion Trees live at The Others, Stoke Newington

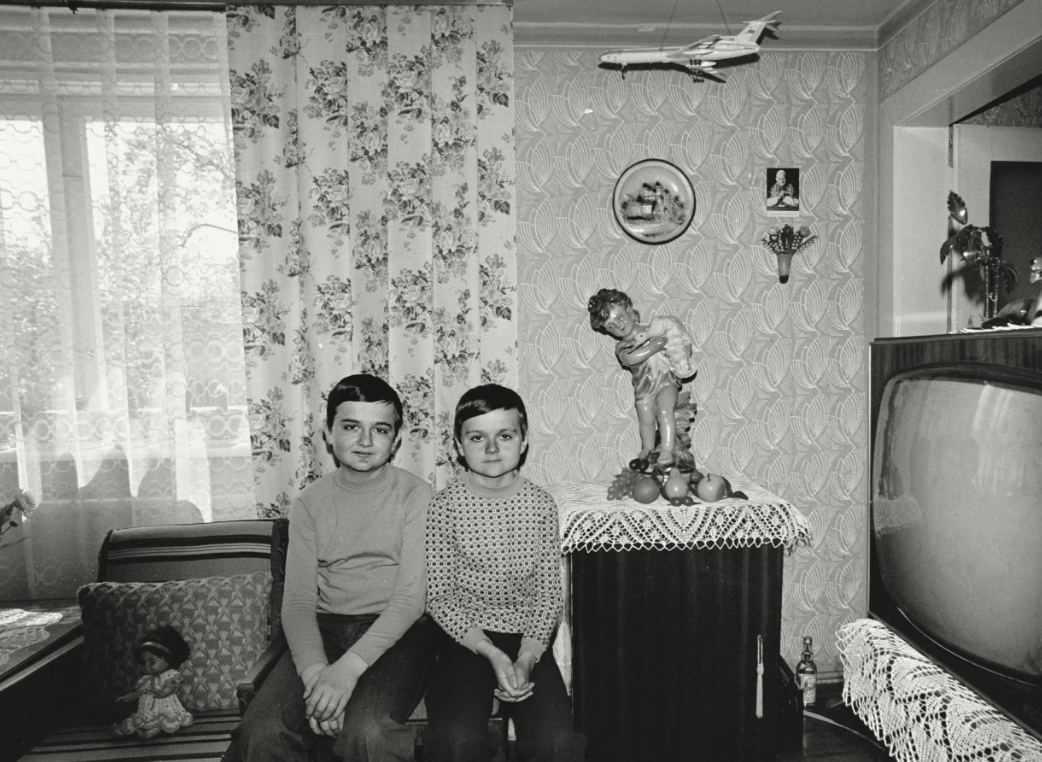

Amy: Zofia Rydet: Sociological Record, The Photographers’ Gallery

Tom: I can't remember how I first discovered South African indie band Champion Trees at the end of last year, but I have not been able to keep quiet about their new album, A Duck's Water Off My Back, since. A saxophone and violin form the melancholic, melodic tapestry on which the clever lyrics weave their emotional threads (reminiscent of Black Country New Road's Ants From Up There). I was resigned to not being able to see them in the flesh for some time, so it was a pleasant surprise to open Instagram one day to be greeted by the announcement of their first gig of 2026, taking place in January in London. Rather than make the 6,000 mile trip to Cape Town, I hopped on the overground for 3 miles to Stoke Newington. The gig showcased lead singer, Francis Christie’s personality, stressed the maturity of their sound, and cemented their status in my mind as talented craftsmen and future stars of the genre.

Amy: Zofia Rydet. A Polish photographer who made it her mission, at the age of 67, to photograph every home in her country. She didn’t stop until her death in 1997, at which point she had taken over 20,000 photographs, many of which remain undeveloped.

As someone with an affinity for interrogating the so-called ordinary, Zofia Rydet is my type of woman. Her photographs feel alive and sensual. Lace curtains, patterned wallpaper, framed images covering the whole wall, wooden crosses, beds squashed up next to the kitchen, toy planes hanging down from the ceiling, kettles on the stove, the pope watching over. I could smell and feel the homes she invited us into. The people she captures stare directly at the camera with a straight face, often from a distance. The framing diminishes the boundary between people and objects, blending them together. Her photographers serve as a reminder that what we choose to surround ourselves with is not a trivial matter, it speaks deeply to who we are as people and as a society.

Zofia’s work doesn’t condescend or patronise, it gives the everyday the serious inquiry it deserves. She works from the belief that the mundane holds secrets and truths just as important as the grandiose.